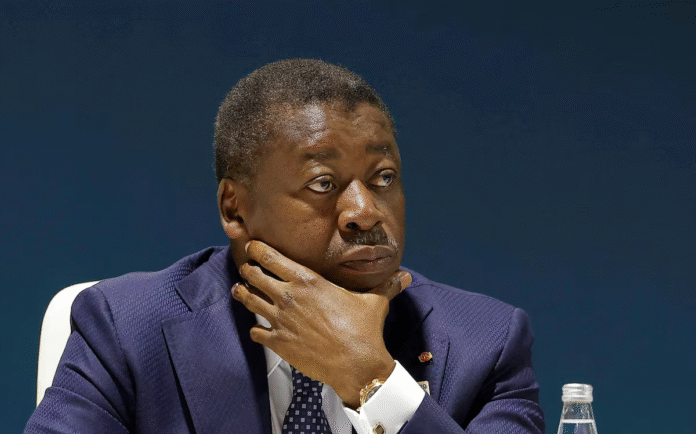

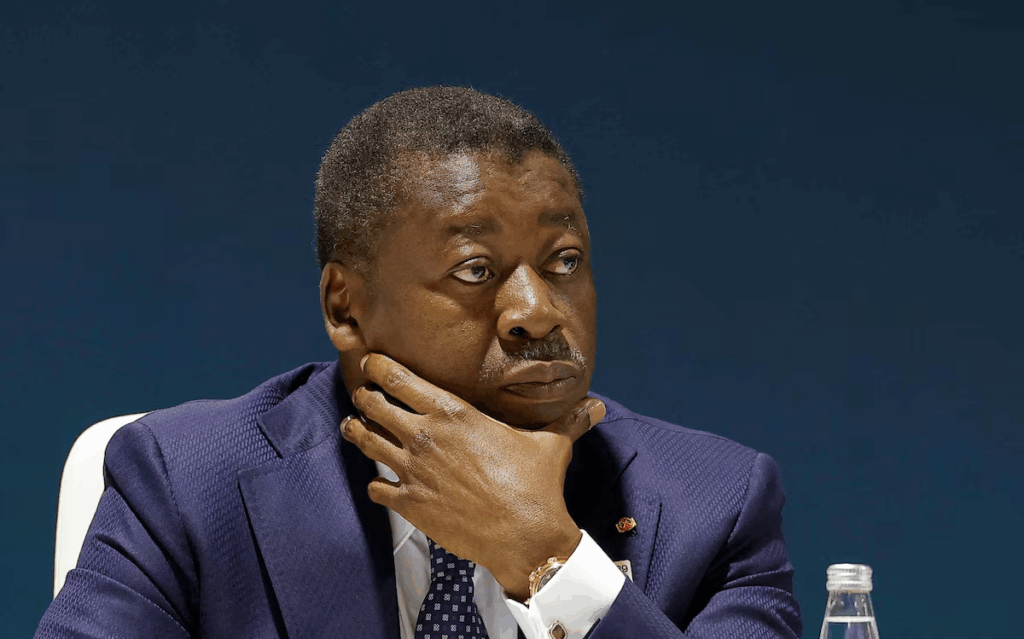

A new constitution that has allowed Togo’s long-time head of state, Faure Gnassingbé, to shift to a new role as all-powerful prime minister – and escape the constraint of presidential term limits – has triggered anger on the streets of the capital, Lomé. Protests are set to continue this Friday.

At least five demonstrators have died while confronting official security forces in recent weeks.

But it is not the orthodox political opposition – predictably crushed in local elections last week – that has mobilised frustrated young Togolese people.

Instead, it is musicians, bloggers and activists who have tapped into popular anger and weariness with a regime that has been in power, under the leadership of Faure Gnassingbé or, before him, his father Gnassingbé Éyadéma, for almost six decades.

That outstrips even Cameroon’s President Paul Biya, 92, – who has just confirmed his intention to stand for an eighth successive term in elections later this year – or Gabon’s father-and-son presidents, Omar Bongo and Ali Bongo, the latter of whom was deposed in a coup in August 2023.

The lessons of that episode did not escape Faure Gnassingbé, a shrewd and often discreet operator who quickly moved to devise a new constitutional structure for Togo, to prolong his own hold on power while playing down his personal profile, in a bid to defuse accusations of dynastic rule.

He will no longer need to stand for re-election in his own name.

The 59-year-old holds the premiership because his Union pour la République (Unir) party dominates the national assembly – and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future, thanks to a constituency map gerrymandered to over-represent its northern heartlands and understate the voting weight of the pro-opposition coastal south.

Gilbert Bawara, Togo’s civil service and labour minister, maintains the 2024 election was above board, with “all the major political actors and parties” taking part.

“The government cannot be held responsible for the weakness of the opposition,” Bawara told BBC Focus on Africa TV last week.

He added that those with a genuine reason to demonstrate could do so within the law, blaming activists abroad for inciting “young people to attack security forces” in an attempt to destabilise the country.

The new constitutional framework was announced at short notice in early 2024 and quickly approved by the compliant government-dominated national assembly. There was no attempt to secure general public approval through a referendum.

A one-year transition concluded this May as Gnassingbé, who had been head of state since 2005, gave up the presidency and was installed in the premiership, a post now strengthened to hold all executive power and total authority over the armed forces.

To occupy the presidency, a role now reduced to a purely ceremonial function, legislators chose the 86-year-old former business minister, Jean-Lucien Savi de Tové.

This reshuffling of the power structure was presented abroad by regime mouthpieces as moving from a strong presidential system to a supposedly more democratic “parliamentary” model – in tune with the traditions of the Commonwealth, which Togo, like Gabon, had joined in 2022, to broaden its international connections and reduce reliance on traditional francophone links with France, the former colonial ruler.

The transition to new constitutional arrangements designed to perpetuate Gnassingbé’s rule passed off almost without outside comment from international partners whose attention is currently focused on Gaza and Ukraine rather than Africa.

Nor was there any complaint from fellow leaders in the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), even after Togo held fresh legislative elections just weeks after the new constitution had been promulgated, in flagrant breach of the regional bloc’s protocol on good governance and democracy, which says that after a change of constitution at least six months must elapse before any major election is held.

Badly shaken by the decision of three military-run countries – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – to quit Ecowas, remaining member governments are reluctant to challenge the behaviour of others in case they follow suit.

But on the streets of Lomé it has been a different matter.

The rapper and regime critic Essowe Tchalla, known by his stage name “Aamron”, released a satirical video calling for the “celebration” of Gnassingbé’s 6 June birthday.

When he was arbitrarily snatched from his home at the end of May by regime security agents and taken to an unknown location, anger surged among young urban Togolese.

Hundreds protested on the streets of the capital on 5 and 6 June and scores were detained by government forces.

The affair took a particularly sinister twist with the discovery that Aamron had been confined to a mental hospital, a measure more reminiscent of the 1970s Soviet Union than West Africa in 2025 – and the subsequent release of a hostage video –style statement in which he was filmed admitting to psychological problems and apologising to Faure Gnassingbé, remarks he has completely disowned after being released without charge.

Meanwhile, late June brought a further wave of street protests, with the security forces confronting youths who had set up burning barricades.

Human rights groups reported widespread random detentions, often of uninvolved passersby, while informal pro-government militia, often armed, roamed the streets in pick-up trucks.

At least five people were killed and two bodies were found in the lagoons north of central Lomé, though whether they had drowned while fleeing arrest or been deliberately killed was unclear.

But it is cultural figures like Aamron – and Honoré Sitsopé Sokpor, a poet known by his alias “Affectio” and jailed in January – who have inspired this latest upsurge in protests. They connect to young popular opinion in a way that conventional politicians cannot.

Indeed, much of the Togolese public appears to have lost faith in the formal political process.

Although the local elections on 17 July passed off quietly, with Unir predictably dominant according to official results, Jean-Pierre Fabre, a leading opposition figure, said there were no other voters in his local polling station when he went to cast his ballot.

Critics see the new constitution as no more than a device to perpetuate the rule of the Gnassingbé dynasty – a regime variously described by West African regional media as a “republican monarchy” and “legalist authoritarianism”.

A leading Togolese human rights activist says popular frustration has reached unprecedented levels.

There have been previous upsurges of mass protest.

In 2017, the churches supported marches demanding reform while a charismatic new opposition figure, Tikpi Atchadam, mobilised young people across the previously regime-dominated centre-north.

In the 2020 presidential election, the regime was taken aback by the strong performance of opposition challenger Agbeyomé Kodjo, who was openly backed by the much-respected 89-year-old former Archbishop of Lomé, Philippe Kpodzro.

Although both men have since died, the political movement inspired by the late cleric remains highly active and is regularly targeted by the authorities.

Now, once again, we are seeing frustration boil over, particularly among young urban Togolese.

With his constitutional revamp to a supposedly “parliamentary” system, Gnassingbé aims to retain full control, yet step his own personality back from the political firing line.

But that particular manoeuvre looks condemned to failure in the face of challenge from creative leaders of popular culture – bloggers, singers and grassroots activists.

On social media, the hashtag #FaureMustGo is now circulating. And recent weeks have seen the launch of a new campaign for change, known as M66, which stands for “6 June Movement” from the date of Gnassingbé’s birthday.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Tags:

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.